Background

Mastitis remains one of the most challenging endemic diseases affecting dairy cows in Ireland and worldwide, both in terms of the cost of production and the welfare of affected cows.

Money spent on things like purchased feed, fuel, fertiliser and medicines is felt directly by dairy farmers. Still, the true cost of sub-optimal health and production is more difficult to measure despite its large impact on a dairy enterprise’s overall profitability.

The current average incidence rate of clinical mastitis is between 47 and 65 cases/100 cows/year.

Cost of mastitis

The total cost of clinical mastitis comprises several components such as milk discard, reduced yields, increased culling, drugs, increased labour and other veterinary costs. The scale of these losses may vary between farms. However, the cost of clinical mastitis typically lies somewhere in the range of 1.5 – 8cpl of the total milk produced on the farm.

As measured by somatic cell count (SCC), subclinical mastitis is associated with increased culling, discarded milk, and reduced milk yields with a typical loss of 0.5 litres of milk/day. As with clinical mastitis, the total cost of subclinical mastitis will vary between farms but is likely to be in the range of 0.2-3.2 cases of milk produced.

Therefore, It is vital that individual farms take the time to calculate what mastitis will likely cost them. As SCC increases, net farm profit decreases. Net farm profitability is reduced from 5.9 cents/kg at SCC of <100,000 cells/ml to 2.3 cents/kg at SCC of >400,000 cells/ml.

| Net farm profit for each SCC category | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCC category (,000 cells/ml) | |||||

| <000 | 100 – 200 | 200 – 300 | 300 – 400 | >400 | |

| Net Farm Profit, € | 31,252 | 26,771 | 19,661 | 16,936 | >400 |

| Difference relative to SCC <100,00 cell/ml | 0 | 4,481 | 11,591 | 14,316 | 19,504 |

When penicillin was introduced in the 1940’s it was assumed that with such an effective treatment, mastitis would soon be eliminated. Unfortunately, this proved not to be the case, and the average incidence rate of clinical mastitis of between 47-65 cases/100 cows/year has not decreased significantly in the last 10-15 years.

The basis of mastitis control is herd management, specifically aimed at reducing the level of bacterial challenge on the teat and teat end and reducing the infection rate. Mastitis can never be eradicated; however, if milking routines and hygiene techniques are improved, then the spread of infection will be reduced.

Spend the extra few seconds ensuring adequate coverage of teat spray – 15ml per cow per spray

Types

Mastitis remains one of the most challenging endemic diseases affecting dairy cows in Ireland and worldwide both in terms of the cost to production and the welfare of affected cows.

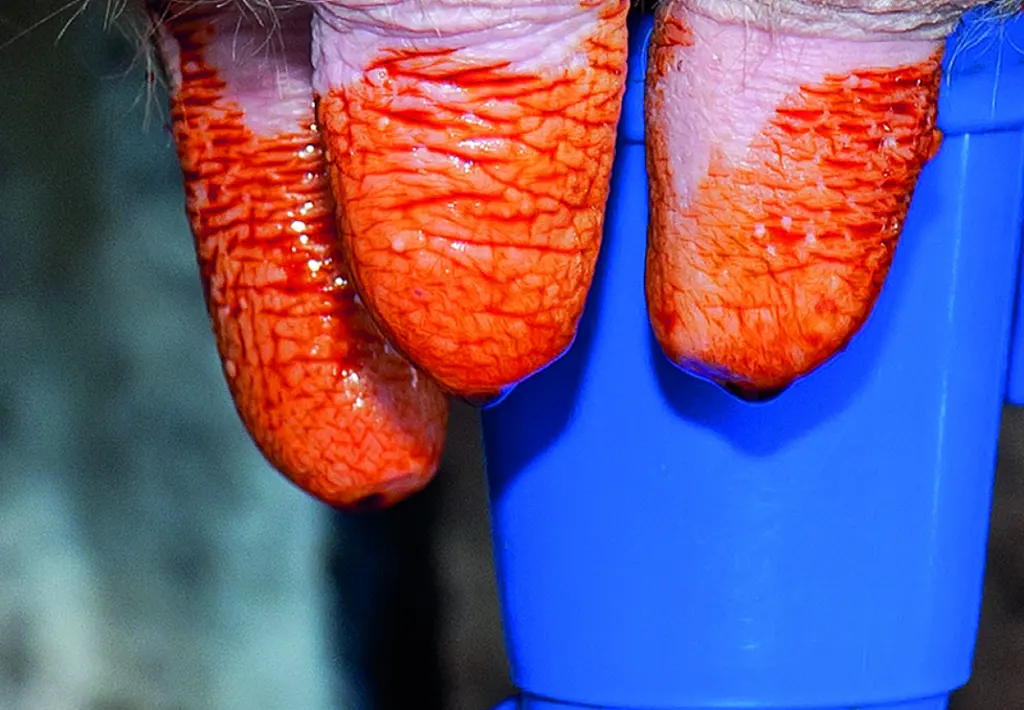

Contagious Mastitis is caused by bacteria such as Staph aureus and Strep. agalactiae being transmitted between cows during milking. Milk from one infected quarter can be spread to the teat skin of other quarters and other cows by milkers’ hands, liners and cross-flow of milk between clusters. Damaged teats/teat ends are particularly susceptible. Poorly maintained milking machines can also contribute to the transmission of infection.

Prevention of contagious mastitis involves keeping teat/teat ends in good condition, disinfection of teats before and after milking, wearing clean gloves during milking, well-maintained milking machines, and good parlour procedures that keep the cows calm.

Environmental Mastitis is caused by bacteria such as E. coli and Strep uberis. The primary sources are faeces and mud. The risk of infection from these bacteria increases when the environment is wet and dirty. Environmental Mastitis Areas where cows congregate, such as water troughs, gateways, collecting yards, and housing, must be kept clean to minimise infection.

Environmental mastitis prevention involves minimising faeces and mud levels in the cows’ environment.

Environmental Mastitis risk increases where cows congregate, such as water troughs, gateways, collecting yards, and housing these areas must be kept clean to minimise infection spread.

Why we must disinfect cows teats?

Bacteria in milk from an infected quarter or on the teat surface from the environment may contaminate milk or many other teats from “clean” cows during milking. Bacteria can multiply on the teat skin and extend into the teat canal, particularly after milking when the teat canal is open. After a liner has milked an infected quarter, bacteria may be transferred to the next 5/6 cows milked with that cluster.

If the whole surface of the teat is cleaned, disinfected and dried Pre Milking and disinfected Post Milking, then the spread of bacteria can be minimised. Teat disinfection also helps to keep teat skin supple and in good condition. Teat disinfection reduces new infections due to contagious mastitis by 50% and is also important in reducing environmental mastitis infections. It is also one of the most effective and sub-clinical mastitis (SCC) control measures available, but it only works if done thoroughly. Failure to cover the whole teat for the complete lactation of every cow during milking is the most common error in teat disinfection.

Ensure the whole teat is covered with disinfectant by spraying upwards from beneath the teats, not from the side. Ensure that the spray pattern of the sprayer gives complete coverage of the whole teat. Dipping is more reliable than spraying for ensuring complete coverage, but it takes longer and with larger herds this is really not an option. We can achieve the same level of coverage when we use film forming teat sprays, and spend the extra few seconds ensuring coverage.

Spend the extra few seconds ensuring adequate coverage of teat spray – 15ml per cow per spray

| Net farm profit for each SCC category | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Application method | Typical Volume of Teat Dip used / ml | ||||

| Spraying | 15 | ||||

| Dipping | 10 | ||||

Thermoduric Bacteria – Although these are not mastitis-causing bacteria, they are highly influential on milk quality and are found on cows teats from the soil during outdoor grazing periods.

Thermoduric bacteria organisms are capable of surviving pasteurisation, so monitoring their presence in milk is important to milk purchasers and processors. Surviving pasteurisation can lead to carry-over into products, causing quality defects (reduction in shelf life) and can cause significant problems for food manufacturers using milk and milk products as a food ingredient.

Using PCS-registered oxidising disinfectants such as Cluster San will reduce spore populations. Non-oxidising biocides will have limited efficacy against spores.

Bacillus and Clostridium are the most common thermoduric species found in silage, faeces, animal bedding and soil. They exist in a very heat-resistant form of spores and are not killed by pasteurisation. This emphasises the importance of limiting their numbers in raw milk through good on-farm hygiene, good milking/parlour procedures and maintaining a high standard of hygiene in the milking equipment and bulk tank.